Falling Cloud (Snake Lake tour, NYC)

Is it a compulsion, or obsession? I can’t visit New York without diving into the museums. Today I visited the Met and the Whitney. The draw at the Met was  the John Baldessari retrospective. One of those godfathers-of-conceptual-art I’ve encountered in bits and pieces, but it was wonderful to take it his entire oeuvre in about an hour. Favorite piece: a 10-photo montage in which he took a map of California and photographed the actual location that each letter covered on the map. The final “A,” for example, was located in Joshua Tree. (It looks more clever than it sounds; which is practically a definition of conceptual art.)

the John Baldessari retrospective. One of those godfathers-of-conceptual-art I’ve encountered in bits and pieces, but it was wonderful to take it his entire oeuvre in about an hour. Favorite piece: a 10-photo montage in which he took a map of California and photographed the actual location that each letter covered on the map. The final “A,” for example, was located in Joshua Tree. (It looks more clever than it sounds; which is practically a definition of conceptual art.)

The last few times I’ve visited the Whitney it’s been a disappointment. Either old stuff I’ve stared at to exhaustion (i.e, Edward Hopper) or new work that  does nothing for me. Right now there’s a retrospective of the indefinable Paul Thek (1933-1988, of AIDS). Much of the work is nightmarish: sculptural representations of hunks of bloody flesh. But the title piece, The Diver, really spoke to me. A painting of a pink figure, diving into translucent blue. Thek, like me, was fascinated by the unknown perils and possibilities contained within lakes and oceans. His artistic perspective originated from above; in Snake Lake, I take the view from below.

does nothing for me. Right now there’s a retrospective of the indefinable Paul Thek (1933-1988, of AIDS). Much of the work is nightmarish: sculptural representations of hunks of bloody flesh. But the title piece, The Diver, really spoke to me. A painting of a pink figure, diving into translucent blue. Thek, like me, was fascinated by the unknown perils and possibilities contained within lakes and oceans. His artistic perspective originated from above; in Snake Lake, I take the view from below.

Did a reading tonight at the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art, one of my favorite places in Manhattan. A modest gathering; most of the people who entered the museum were there to hear a talk by film director Mike Nichols. But I gave it up for my attentive little group, and as always found myself totally immersed in the rarefied world of storytelling – which, paradoxically, seems a transit beyond the ego, an almost divinely guided ascent into a jet stream of urgent communication. (One does wish, afterwards, that more people had been there to enjoy it.) Only six people left with snakes—and they were very lucky people.

Throne. Every King needs one of these, and this one is a beauty. More than half a ton of silver and a 30 tolas of gold (nearly a pound) were used to build the sofa-sized, velvet-cushioned seat of power. A canopy of nine gold nagas shaded the King’s head, and thick gold serpents served as his armrests.

Throne. Every King needs one of these, and this one is a beauty. More than half a ton of silver and a 30 tolas of gold (nearly a pound) were used to build the sofa-sized, velvet-cushioned seat of power. A canopy of nine gold nagas shaded the King’s head, and thick gold serpents served as his armrests. On June 1st, 2001,

On June 1st, 2001,

accumulate destinations”¦ Above my desk hung a map of the United States, stuck full of pins, heavy with the destination voodoo of the post-Kerouac generation. On the Road was practically mythology to me; I charted Sal Paradise’s route through bop America as a scholar of ancient Greek might try to trace Odysseus’s travels.

accumulate destinations”¦ Above my desk hung a map of the United States, stuck full of pins, heavy with the destination voodoo of the post-Kerouac generation. On the Road was practically mythology to me; I charted Sal Paradise’s route through bop America as a scholar of ancient Greek might try to trace Odysseus’s travels. It wasn’t even my idea.

It wasn’t even my idea. and kids’ toys, a black SUV and a couple of bright red trash bins parked in front, the trees nearly empty now, it being Fall, and a melancholy pre-Thanksgiving light pervading the alley like the memory of hot cider on those short afternoons after football practice at Lowell High, itself as angular and sharply-lit as a canvas by Hopper, or de Chirico, near enough to the Mills so that the boys and girls could hear their mothers at work”¦.

and kids’ toys, a black SUV and a couple of bright red trash bins parked in front, the trees nearly empty now, it being Fall, and a melancholy pre-Thanksgiving light pervading the alley like the memory of hot cider on those short afternoons after football practice at Lowell High, itself as angular and sharply-lit as a canvas by Hopper, or de Chirico, near enough to the Mills so that the boys and girls could hear their mothers at work”¦.

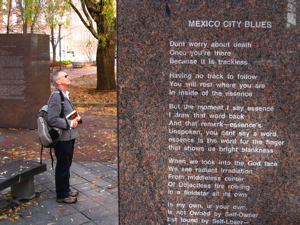

or Mexico itself, though we know he loved his roots and family and was a popular kid in high school, athletic and smart. What I mean is that Lowell meant more to Kerouac than to us, and although his bones lay beneath our feet I realized that if I can say one thing about Jack Kerouac it is that he is not interred. He is what Melville called a “loose fish,” connected not so much to this place (or any place) but to the Sense of Place itself, having created and cultivated that beautiful abstract sensibility better than anyone: that sweet lonely balance of longing and belonging, abiding in the moment while utterly aware of mortality, sublimely grateful yet inconsolably sad.

or Mexico itself, though we know he loved his roots and family and was a popular kid in high school, athletic and smart. What I mean is that Lowell meant more to Kerouac than to us, and although his bones lay beneath our feet I realized that if I can say one thing about Jack Kerouac it is that he is not interred. He is what Melville called a “loose fish,” connected not so much to this place (or any place) but to the Sense of Place itself, having created and cultivated that beautiful abstract sensibility better than anyone: that sweet lonely balance of longing and belonging, abiding in the moment while utterly aware of mortality, sublimely grateful yet inconsolably sad.

This is a funny thing about being a freelance journalist; one becomes semi-expert on subjects that, a week or a month or a year ago, one knew nothing about. Like the rest of the world (with the exception of a few people on the island itself), my entire idea of what a Tassie Devil looked like was based on the Looney Tunes character, Taz.

This is a funny thing about being a freelance journalist; one becomes semi-expert on subjects that, a week or a month or a year ago, one knew nothing about. Like the rest of the world (with the exception of a few people on the island itself), my entire idea of what a Tassie Devil looked like was based on the Looney Tunes character, Taz.