Growing up on Long Island, I had map fever. It was more than a compulsion to cover my walls; it was a need to possess the places those maps represented, to

accumulate destinations”¦ Above my desk hung a map of the United States, stuck full of pins, heavy with the destination voodoo of the post-Kerouac generation. On the Road was practically mythology to me; I charted Sal Paradise’s route through bop America as a scholar of ancient Greek might try to trace Odysseus’s travels.

In 1974, after two years at a local college, I set off for the West Coast at last, attempting to duplicate Kerouac’s journey and follow that “one long red line called Route 6 that led from the tip of Cape Cod clear to Ely, Nevada, and there dipped down to Los Angeles.” Needless to say, my path across the country took its own shape. It included some of the cities Sal Paradise visited, like Chicago and Denver, but for the most part I wound my way through territories unknown, an eager disciple of the Fates that steer young travelers into unexpected–but always strangely appropriate–encounters”¦.

– from “On Maps,” Scratching the Surface

Don’t know why it took me so long, but it wasn’t until this November — after giving a talk at the 100th Anniversary celebration of Hostelling International in Boston — that I finally made the pilgrimage to Lowell, Massachusetts, to visit Jack Kerouac’s grave.

It wasn’t even my idea. The inspiration came from Tony Wheeler, the co-founder of Lonely Planet, who was also speaking at the event. Along with travel writer Rolf Potts (and his Arlington-based friend Steve, who served as our own private Dean Moriarty) we left our hotel near the Boston Common and drove the 45 minutes out to the old milling town where America’s most poetic vagabond was born, schooled, and laid to rest.

It wasn’t even my idea. The inspiration came from Tony Wheeler, the co-founder of Lonely Planet, who was also speaking at the event. Along with travel writer Rolf Potts (and his Arlington-based friend Steve, who served as our own private Dean Moriarty) we left our hotel near the Boston Common and drove the 45 minutes out to the old milling town where America’s most poetic vagabond was born, schooled, and laid to rest.

There’s nothing much to say about the house Kerouac was born in, at 9 Lupine Road. It’s a brown shingle two story (his family lived in the top flat) with a porch filled with hanging plants  and kids’ toys, a black SUV and a couple of bright red trash bins parked in front, the trees nearly empty now, it being Fall, and a melancholy pre-Thanksgiving light pervading the alley like the memory of hot cider on those short afternoons after football practice at Lowell High, itself as angular and sharply-lit as a canvas by Hopper, or de Chirico, near enough to the Mills so that the boys and girls could hear their mothers at work”¦.

and kids’ toys, a black SUV and a couple of bright red trash bins parked in front, the trees nearly empty now, it being Fall, and a melancholy pre-Thanksgiving light pervading the alley like the memory of hot cider on those short afternoons after football practice at Lowell High, itself as angular and sharply-lit as a canvas by Hopper, or de Chirico, near enough to the Mills so that the boys and girls could hear their mothers at work”¦.

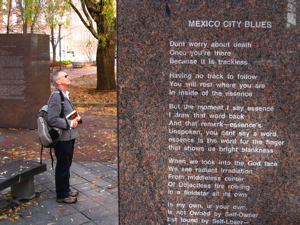

These days you can walk from the Boott Cotton Mill and Museum (now, strangely, a National Historic Park) to the Kerouac Memorial: a series of marble pillars arranged as a cross and a mandala, inscribed with passages from the Beat hero’s books and poems:

–When you’ve understood this scripture, throw it away. If you can’t understand this scripture, throw it away. I insist on your freedom.

– The Scripture of the Golden Eternity, #45

Two miles south of Lowell along a road punctuated by Dunkin’ Donuts and freight car diners and gas stations without restrooms is the Edson Cemetery. We parked inside the wrought iron gate and crunched through vivid leaves, a jazzy honeyed medley of cinnamon red, candy corn yellow and burnt umber.

It was a big cemetery. There was no map. Finally — with the help of Steve’s iPhone, God bless “˜em — we found the flat stone. It was covered with a scattering of small offerings: dried flowers, cigarette packs, stones, candles, an American flag, a picture of Buddha, hand-written notes.

We stood there for a while and didn’t know what to say. Kerouac’s marker may be here — but for us his spirit still inhabits the road, anchored more in San Francisco or Denver  or Mexico itself, though we know he loved his roots and family and was a popular kid in high school, athletic and smart. What I mean is that Lowell meant more to Kerouac than to us, and although his bones lay beneath our feet I realized that if I can say one thing about Jack Kerouac it is that he is not interred. He is what Melville called a “loose fish,” connected not so much to this place (or any place) but to the Sense of Place itself, having created and cultivated that beautiful abstract sensibility better than anyone: that sweet lonely balance of longing and belonging, abiding in the moment while utterly aware of mortality, sublimely grateful yet inconsolably sad.

or Mexico itself, though we know he loved his roots and family and was a popular kid in high school, athletic and smart. What I mean is that Lowell meant more to Kerouac than to us, and although his bones lay beneath our feet I realized that if I can say one thing about Jack Kerouac it is that he is not interred. He is what Melville called a “loose fish,” connected not so much to this place (or any place) but to the Sense of Place itself, having created and cultivated that beautiful abstract sensibility better than anyone: that sweet lonely balance of longing and belonging, abiding in the moment while utterly aware of mortality, sublimely grateful yet inconsolably sad.

Rolf left a dollar bill he’d been carrying for six years, since he got it as change at the Golden Gate Bridge tool booth in 2003. Tony left a $10 trillion note that he’d picked up in Zimbabwe.

I dropped three coins onto the stone. They fell heads, heads, tails. The I Ching value of eight: a broken highway line. “The dark, yielding, receptive power of yin.”

Thank you, Jack Kerouac, I whispered to the bare trees in the leaf-littered November Lowell cemetery. We’re here by your invitation.